The Parable of Lazarus and the Rich Man: A Prophetic Indictment of Religious Corruption

Jesus' parable of Lazarus and the Rich Man offers a sharp critique of religious corruption, targeting Caiaphas, the high priest. This prophetic message challenges us to confront spiritual blindness, prioritize compassion, and embrace true heart transformation.

1. Introduction

Jesus' parable of Lazarus and the Rich Man in Luke 16 has often been interpreted as a lesson on wealth and the afterlife. However, when examined closely, this parable reveals a much more targeted prophetic message. Through study, we uncover a prophetic indictment aimed at the religious elite of Jesus' day—particularly Caiaphas, the high priest.

This historically grounded interpretation cuts to the heart of the true systemic corruption within the religious institutions and religious ruling class of the time. It's a message that resonates powerfully in our contemporary world, where misuse of religious and political power remains all too common.

By identifying Lazarus as the man Jesus would later raise from the dead and the rich man as Caiaphas, we uncover layers of meaning that go beyond traditional interpretations. Our exploration will reveal compelling evidence from scripture, historical sources, and symbolic analysis:

- The prophetic foreshadowing of Lazarus' resurrection and its rejection

- The symbolic significance of the rich man's purple garments and luxurious lifestyle

- The historical context of Caiaphas' role as high priest and his involvement in Jesus' trial

This parable serves as a prophetic foreshadowing of Jesus' own ministry, death, and resurrection, offering insight into the depth of opposition He faced and the ultimate vindication of His message.

In today's world, where religious institutions still struggle with corruption and the gap between rich and poor continues to widen, this parable challenges us to examine our own hearts. It asks us whether we, like Caiaphas, might be cloaking spiritual poverty with outward signs of piety and success, all while ignoring the suffering at our very gates.

Join us as we unravel the intricate threads of this parable, discovering its relevance not only for Jesus' immediate audience but for all who seek to understand the true nature of faith, compassion, and spiritual transformation in our contemporary world.

2. The Rich Man as Caiaphas: Historical and Scriptural Evidence

The Rich Man's Identity: Caiaphas the High Priest

While Jesus doesn't explicitly name the rich man in the parable, there are several compelling pieces of evidence that suggest he represents Caiaphas, the high priest at the time:

Priestly Garments and Outward Appearances

Luke 16:19 describes the rich man as clothed in "purple and fine linen." This is not merely a description of wealth, but a direct reference to priestly garments. Exodus 28:5-6 specifies that the ephod worn by the high priest was to be made of "gold, blue, purple and scarlet yarn, and fine linen." This specific detail points to the rich man's identity as a high-ranking priest. Purple, a color associated with royalty and wealth due to the expense of purple dye, was specifically prescribed for the high priest's garments, symbolizing his elevated status[1].

Key Insight: Caiaphas' luxurious garments and daily indulgence are symbolic not just of his personal wealth, but of the larger religious system's failure to care for the poor and oppressed, as represented by Lazarus.

The symbolism of these garments runs deep. While they were meant to signify holiness and dedication to God's service, in this parable they represent the stark contrast between outward appearances and inner corruption. Jesus often criticized such hypocrisy, famously comparing the Pharisees to "whitewashed tombs" in Matthew 23:27 - beautiful on the outside but full of death within.

Wealth and Corruption in the Temple System

The parable states that the rich man "lived in luxury every day" (Luke 16:19). Historical sources provide insight into the opulent lifestyle of the high priestly families. Josephus, in his "Antiquities of the Jews" (20.9.2), records that Annas, Caiaphas' father-in-law, used his position to control temple sacrifices, establishing lucrative markets known as "Annas' Bazaars." These markets exploited the poor, forcing them to buy sacrificial animals at inflated prices[2].

The Talmud likewise criticizes the corruption of the high priesthood, noting how Annas' family wielded immense financial and political power at the expense of the people (Pesachim 57a). It states, "Woe is me because of the house of Hanan [Annas], woe is me because of their whisperings!" - a clear indictment of their corrupt practices[3].

Family Connections and Political Power

In Luke 16:28, the rich man mentions his five brothers. This detail aligns with historical records that Annas had five sons, all of whom served as high priests at various times. This family connection further solidifies the link between the rich man and the priestly dynasty of which Caiaphas was a part[4].

Notably, the corruption within this family extended beyond Caiaphas. Historical records indicate that another of Annas' sons, Ananus ben Ananus, was responsible for the murder of James, Jesus' brother, years after Jesus' crucifixion[5]. This shocking event further demonstrates the deep-rooted spiritual blindness and abuse of power within this influential family, lending even more weight to Jesus' critique in the parable.

The persistence of such corruption across generations underscores the systemic nature of the problem Jesus was addressing. It wasn't just about individual failings, but about a deeply entrenched system of religious and political power that had strayed far from its divine purpose.

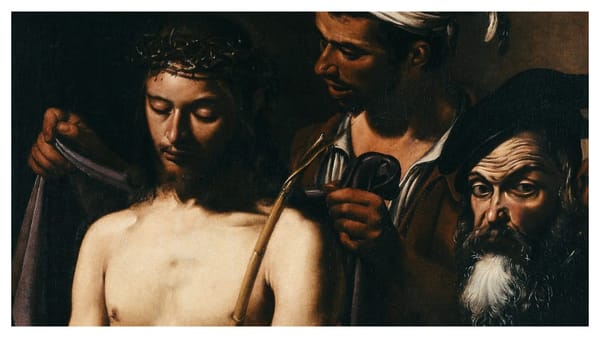

Caiaphas' Role in Jesus' Trial and Crucifixion

As high priest during one of the most politically tumultuous periods in Judea's history, Caiaphas held immense power both religiously and politically. His collaboration with the Roman authorities and his control over temple practices enabled him to maintain a level of wealth and influence far beyond what the Law intended for the priesthood[6].

Caiaphas played a central role in the trial and crucifixion of Jesus. John 11:49-52 records Caiaphas' infamous statement that it would be better for one man to die for the people than for the whole nation to perish. This cynical political calculation reveals the corrupt mindset that Jesus critiques in the parable.

Furthermore, Caiaphas was the high priest who handed Jesus over to Pilate (Matthew 26:57-68, John 18:13-14, 24, 28). His actions in these pivotal moments of Jesus' life underscore the rich man's deeper connection to the religious and political corruption that Jesus was critiquing in His ministry.

By identifying the rich man as Caiaphas, Jesus' parable takes on a much sharper edge. It becomes not just a general warning about the dangers of wealth and indifference to the poor, but a specific prophetic indictment of the high priestly office and its failure to fulfill its sacred duties. This interpretation adds significant depth to our understanding of Jesus' conflict with the religious authorities and His call for genuine spiritual transformation.

3. The Lazarus Connection: Scriptural and Symbolic Evidence

Is Lazarus in the Parable the Same Lazarus Raised by Jesus?

While some scholars argue that "Lazarus" was simply a common name and the parable's character is fictional, there is compelling evidence to suggest otherwise. This interpretation not only connects the parable to a real figure but also amplifies the prophetic message Jesus was delivering to His audience.

Prophetic Foreshadowing and Real-Life Parallels

In Luke 16:31, Jesus concludes the parable with Abraham saying, "If they do not listen to Moses and the Prophets, they will not be convinced even if someone rises from the dead." This statement eerily foreshadows the actual raising of Lazarus in John 11:43-44, and the subsequent rejection of this miracle by the religious leaders.

"In this parable, Jesus does not merely offer a critique of one man; He speaks prophetically to an entire system of corruption within the religious leadership. As the prophet who would soon face the full force of this corruption at His own trial, Jesus' words here carry the weight of divine judgment against the system that had failed its people."

Moreover, this foreshadowing extends to the real-life rejection of Jesus after Lazarus was raised. John 12:10-11 records that the chief priests made plans to kill Lazarus as well, because many were believing in Jesus because of him. This parallel between the parable and actual events underscores Jesus' prophetic insight into the hardness of heart among the religious elite.

Beyond the prophetic elements, the parable's details about Lazarus offer rich symbolic meaning.

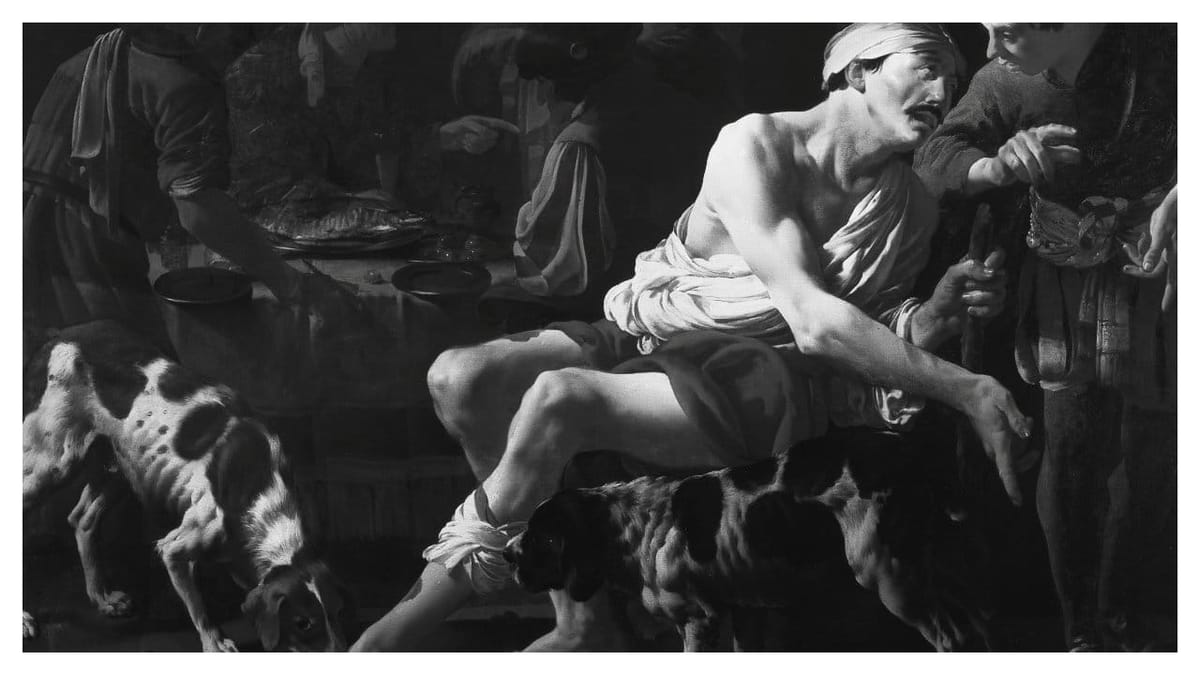

Symbolic Illness and Spiritual Affliction

The parable describes Lazarus as "covered with sores" (Luke 16:20). This detail aligns with the illness that befell Lazarus of Bethany, as reported by his sisters Mary and Martha in John 11:1-3. The Greek word used for "sores" (ἕλκος, helkos) can also be translated as "ulcers" or "wounds," symbolizing not just physical ailment but spiritual affliction.

In Jesus' teachings, physical ailments often symbolized spiritual conditions. The sores of Lazarus in the parable could represent the spiritual suffering of the poor and marginalized, whom Jesus often associated with being "poor in spirit" (Matthew 5:3). This adds a layer of meaning to the parable, suggesting that Lazarus represents not just an individual, but a class of people overlooked by the religious establishment.

The Significance of Names in Jesus' Teaching

In Hebrew, "Lazarus" is derived from "Eleazar," meaning "God has helped." Jesus' deliberate use of this name in the parable, rather than a generic term like "poor man," may be intentional, pointing to the literal Lazarus he would soon raise.

The name itself becomes a statement of faith and a challenge to the rich man (Caiaphas). While the rich man fails to help Lazarus, the name declares that God Himself will help. This foreshadows both the raising of Lazarus from the dead and Jesus' own resurrection, emphasizing God's power to overturn human judgments and expectations.

By linking the parable's Lazarus to the historical Lazarus, Jesus not only demonstrates his foreknowledge but also sets the stage for a powerful critique of those who would reject even the most dramatic evidence of God's power and call to repentance. This interpretation transforms the parable from a simple moral tale into a prophetic narrative that would soon play out in real life, challenging the religious leaders' spiritual blindness and hardness of heart.

Furthermore, this connection invites us to consider how we might, like the religious leaders of Jesus' time, overlook or dismiss the "Lazaruses" in our midst—those who suffer physically or spiritually while we enjoy comfort and status. It challenges us to examine our own hearts and actions, asking whether we truly embody the compassion and love that Jesus calls us to demonstrate.

4. The Delicate Balance: Why Jesus Used Parables

Understanding why Jesus chose to critique the high priest through parables rather than direct condemnation adds crucial context to our interpretation of this story. Caiaphas, as the high priest, was not only a religious figure but also a political one, closely tied to Roman authority. A direct attack on Caiaphas could have had severe implications:

- Sedition against Rome: Caiaphas was a key political figure, appointed by Roman authorities. Directly condemning him might have been viewed as a challenge to Roman rule.

- Alienating devout Jews: Many Jews, despite corruption in the temple, still respected the office of the high priest. A direct confrontation could have caused Jesus to lose credibility with a large portion of His audience.

- Premature conflict with authorities: Jesus had a specific timeline for His ministry, leading up to His crucifixion. Openly attacking Caiaphas might have accelerated His arrest and disrupted His broader mission.

- Overshadowing His broader message: Direct criticism of the high priest might have shifted the focus from Jesus' primary message about the Kingdom of God to a political or personal vendetta.

By using parables, Jesus struck a delicate balance. He was able to deliver:

- A message of judgment and a call for repentance: Without naming names, Jesus was able to call out the corruption of Caiaphas and other religious leaders.

- Plausible deniability: Parables allowed Jesus to convey profound truths without giving the authorities grounds to accuse Him of sedition.

- The possibility of repentance: By leaving the interpretation of His parables open-ended, Jesus left room for even the most powerful figures, like Caiaphas, to reflect and potentially change their ways.

- Focus on spiritual transformation: The indirect nature of parables ensured that the focus remained on heart transformation and the broader message of the Kingdom of God.

This approach of using parables to convey difficult truths was a hallmark of Jesus' teaching style, allowing Him to engage listeners' minds and hearts without immediately triggering defensive reactions. This nuanced approach aligns with Jesus' overall ministry, where He often used indirect teachings to challenge the status quo without inciting premature conflict. It allowed His message to spread and take root while still confronting the injustices and corruption of His time.

Importantly, when Jesus delivered this parable, His "time had not yet come" (John 7:6). This veiled approach allowed Him to challenge the religious order without outrightly provoking confrontation. It was a strategic choice that maintained the delicate balance between confronting corruption and preserving the divinely appointed timeline for His ministry and ultimate sacrifice.

The progression of Jesus' ministry is significant here. While He used parables like that of Lazarus and the Rich Man earlier in His ministry, we see a marked shift in His approach as His "time" drew near. In the days before His final Passover, Jesus delivered His ultimate indictment of the scribes and Pharisees with the series of "Woes" recorded in Matthew 23. This shift from veiled critique to open condemnation demonstrates the careful timing and escalation of Jesus' confrontation with the religious authorities.

In the parable of Lazarus and the Rich Man, Jesus offers a stark warning about the consequences of spiritual corruption and neglect of the poor, while still leaving room for His listeners—including the religious authorities—to reflect and potentially change their ways. This approach exemplifies Jesus' wisdom in navigating the complex religious and political landscape of His time, all while staying true to His mission and the timing of His Father's plan. The parable serves as a precursor to His final, more direct confrontations, showing the patient yet purposeful nature of Jesus' ministry.

5. Conclusion: Jesus, The True High Priest

The parable of Lazarus and the Rich Man, when understood through the lens of historical figures and prophetic critique, reveals itself to be far more than a simple moral tale about wealth and poverty. By connecting the characters to Lazarus of Bethany and Caiaphas the high priest, Jesus delivers a pointed indictment of religious corruption and spiritual blindness. However, the parable’s significance extends beyond critique. It invites us to reflect on the stark contrast between Caiaphas, the corrupt high priest, and Jesus, our true High Priest, who embodies everything a spiritual leader should be.

Caiaphas vs. Jesus: A Study in Contrasts

As the high priest, Caiaphas occupied one of the most revered positions in Jewish society, responsible for mediating between God and His people. Yet, as portrayed in the parable and historical accounts, Caiaphas embodies the corruption of religious authority:

- Clothed in purple and fine linen, living in luxury

- Neglecting the poor and suffering at his very gate

- Using his position for personal gain and political maneuvering

- Ultimately rejecting God’s message, even in the face of miraculous evidence

In contrast, Jesus exemplifies the true nature of spiritual leadership, as beautifully articulated by the Apostle Paul in Philippians 2:6-10:

"Who, being in the form of God, thought it not robbery to be equal with God: But made himself of no reputation, and took upon him the form of a servant, and was made in the likeness of men: And being found in fashion as a man, he humbled himself, and became obedient unto death, even the death of the cross. Wherefore God also hath highly exalted him, and given him a name which is above every name: That at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, of things in heaven, and things in earth, and things under the earth;"

Jesus, as the true High Priest, fulfills the ultimate role of a mediator between God and humanity. Unlike the corrupt priesthood exemplified by Caiaphas, Jesus’ priesthood is characterized by humility, obedience, and sacrificial love, as foretold in Scripture and affirmed in His life and death. This True High Priest provides a living example of:

- Humility, choosing to empty Himself and take the form of a servant

- Selfless love, identifying with the poor and suffering

- Obedience to God’s will, even to the point of death on a cross

- Ultimate self-sacrifice for the sake of others

As Jesus Himself said, "Greater love has no one than this: to lay down one’s life for one’s friends" (John 15:13). This statement finds its fullest expression in Christ’s sacrificial death, the ultimate act of a True High Priest on behalf of His people.

The Call to Transformation

This parable, seen in the light of Christ’s example, calls us to a radical transformation that goes far beyond mere charitable giving or moral living. It challenges us to embody the spirit of Christ, the true High Priest:

- To clothe ourselves in humility rather than the purple of pride and self-importance

- To see and serve the "Lazaruses" at our gates, recognizing Christ in the least of these

- To use whatever position or influence we have for the benefit of others, not personal gain

- To be open to God’s message and transformative work, even when it challenges our comfort or status

This transformation calls us not only to personal change but to communal action—where our humility, service, and love extend to the broader world, embodying Christ’s presence in our families, communities, and workplaces. It invites us to be agents of change, reflecting the love and sacrifice of our True High Priest in all aspects of our lives.

In a world still grappling with inequality, religious formalism, and spiritual complacency, this parable remains a powerful call to radical love and service today. It invites us, in this moment, to follow in the footsteps of our True High Priest, who poured Himself out completely for the sake of others.

As we reflect on this parable and Christ’s example, let us ask ourselves: Where have I clung to pride or self-importance instead of embracing humility? How can I more intentionally serve those in need around me, recognizing Christ in "the least of these"? By heeding this call to Christlike love and service, we honor Jesus, our true High Priest, and actively participate in His ongoing work of redemption and restoration in our world.

May this parable inspire us to live out the transformative power of Christ’s love, becoming channels of His grace and instruments of His peace in a world that desperately needs the example of true, selfless leadership. As we do so, we not only honor our true High Priest but also participate in His ongoing mission of bringing hope, healing, and reconciliation to a broken world.

Footnotes

Milgrom, J. (1996). "Colors and Symbolism in Ancient Israel." In M. Haran (Ed.), Pomegranates and Golden Bells: Studies in Biblical, Jewish, and Near Eastern Ritual, Law, and Literature in Honor of Jacob Milgrom (pp. 49-65). Eisenbrauns. ↩︎

Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 20.9.2 ↩︎

Babylonian Talmud, Pesachim 57a ↩︎

Schürer, E., Vermes, G., & Millar, F. (1973). The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ: Volume II. T&T Clark. ↩︎

Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 20.9.1 ↩︎

Bornkamm, G. (1960). Jesus of Nazareth. Harper & Brothers.t ↩︎